An illness and a joy

The reality (however relative) and nature of time appear inexorable and inescapable. One way to cope with this fact is to tell others and share with them our thoughts, feelings and stories – a bit like unity in the face of a common enemy.

“For whom am I writing this?” wonders

eighty-two year old Iris Chase Griffen in Margaret Atwood’s The Blind Assassin. “For myself? I think

not. I have no picture of myself reading it over at a later time, later time

having become problematical. For some stranger, in the future, after I’m dead?

I have no such ambition, no such hope.”[i] Many

of us are afflicted by this bug for writing – writing in some form or the

other, dashing off letters, composing something creative and, if nothing else,

at least keeping diaries and journals. George Orwell thought that there were

four great motives for writing and they are to be found to different degrees in

every writer. We were firstly driven to write by “sheer egoism”, a “desire to

seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death.”[ii]

Some wrote when they perceived beauty in the external world or “in words and

their right arrangement”. There was also the “historical impulse,” a wish to

identify truths from the past and store them for posterity. Lastly, there was

“political purpose,” to aspire to push the world in a certain direction.

|

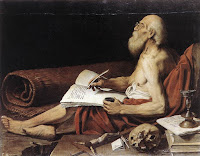

| Leonello Spada, St Jerome, 1610. |

However, aspiring to be the next Orwell does

not always have to be the sole reason for us to write – and presumably not

every one of us is afflicted by hypergraphia either. For most, the overwhelming

driver seems to be to pause the clock: we wish the “horses of the night” would

“run slowly, slowly” as Ovid implored. When someone gets close to death, he

will – as the Czech poet Miroslav Holub observes in his poem, “Metaphysics” –

start collecting things, such as beer coasters from bars “by which he achieves

some immortality, the only kind that's really intelligible.”[iii]

It is as if we are compelled to leave behind these fossils for a future

palaeontologist to pore over and decipher what made us tick. Atwood’s Iris

thinks that we want to “memorialize ourselves… and assert our existence, like

dogs peeing on fire hydrants.” We do this because “at the very least we want a

witness. We can’t stand the idea of our own voices falling silent finally, like

a radio running down.”[iv]

Umberto Eco expressed the same fear of the eventual silence and final darkness when he observed, “What a waste, decades spent building up experience, only to throw it all away… We remedy the sadness by working. For example, by writing…”[v]

Umberto Eco expressed the same fear of the eventual silence and final darkness when he observed, “What a waste, decades spent building up experience, only to throw it all away… We remedy the sadness by working. For example, by writing…”[v]

Our voices will fall silent when time stops

forever for us. It appears that we invented time when we acquired cognition and

intelligence and became aware of the beauty and pleasures around us and, more

importantly, gained the realisation that one day we will have to leave all this

behind us. We meanwhile try to comprehend temporality by attributing some familiar

quanta of events to the past and hope there is a lot more of such events to

come. Animals on the other hand do not seem to have a need for a concept called

time as they live in the here and now. We humans have instead become slave to a

creature of our own making.

Some scientists and philosophers contend

that we do not have to be so worried about the erosion of time for after all

time is an illusion. The arrow of time – and time’s supposed travel only

towards the future – is an effect of the second law of thermodynamics which

imprints on the world “a conspicuous asymmetry between past and future

directions along the time axis…. and talk of past or future is as meaningless

as referring to up or down,” as explained in a recent Scientific American article.[vi] It

is also conted that time emerges “from some timeless stuff that brings itself

to order,” just as life emerges from lifeless molecules.[vii] In

Hindu philosophy, Advaita Vedanta teaches that Brahma, the Absolute, is

timeless, eternal with no before and after. The Bhagavad Gita explains that

when necessary God appears on Earth “as Time, the waster of the peoples”.[viii]

Consequently, the temporal, though real within human experience, has no

ultimate reality. As the Psalm says, “for a thousand years in thy sight are but

as yesterday when it is past, and as a watch in the night.”[ix]

Nevertheless, the only idea of time I am intuitively

wary of - and intrinsically conscious of is the finite nature of my time. Classical science may claim

that natural processes are reversible but I have not witnessed a broken glass re-morphing

into a full one. At a moment of immutable loss – such as the death of someone

close to me - science and philosophy fail to console me. Time, for me, always

flows forward. (It may occasionally appear to stand still when the cline of

time seemingly takes a breather when moments of extreme stress, horror or

sorrow assail me.) The past does not prepare me for such moments when I have

torn my moorings and am adrift. The future too is a blank as I have seemingly

lost all my maps and signposts. Hence, the time I feel in my bones either flows

forward or stands still – but never backwards.

The reality (however relative) and nature

of time appear inexorable and inescapable. One way to cope with this fact is to

tell others and share with them our thoughts, feelings and stories – a bit like

unity in the face of a common enemy. Our writing may not always be assured of

being eloquent, praiseworthy or beautiful; even the very process could moreover

be enervating too. As essayist and literary critic Simon Leys notes, writing is

something that “can be a compulsion, an art, an illness, a therapy, a joy, a

mania, a blessing, a madness, a curse, a passion, and many other things besides.”[x] When

we apply all these adjectives to life too we realise that writing could be a

metaphor for the entirety of life itself.

[i] Margaret Atwood, The

Blind Assassin, Bloomsbury, 2000, p. 43.

[ii] George

Orwell, “Why I write”, http://orwell.ru/library/essays/wiw/english/e_wiw

[iii] Miroslav

Holub, Metaphysics, trans: David

Young,

Grand Street, No. 52, Games (Spring,

1995), p. 60

[iv] Margaret

Atwood, The Blind Assassin,

Bloomsbury, 2000, p. 95.

[v]

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2007/oct/27/society.umbertoeco

[vi] Scientific American

Editors (2012-11-30). A Question of Time: The Ultimate Paradox (Kindle

Locations 260-264). Scientific American. Kindle Edition.

[vii] Scientific American

Editors (2012-11-30). A Question of Time: The Ultimate Paradox (Kindle

Locations 2531-2540). Scientific American. Kindle Edition.

[viii] Aldous Huxley, The Perennial

Philosophy,HarperPerennial, 1945, p.191.

[ix] Psalm

90:4.

[x] Simon Leys, “The Hall of

Uselessness: Collected Essays”, New York Review Books, 2011, p. 267.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment